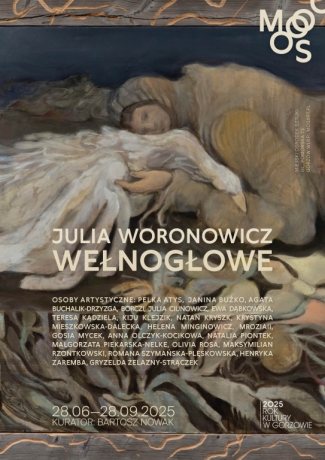

JULIA WORONOWICZ - WEŁNOGŁOWE

Otwarcie: 28.06.2025, godz. 17:00

Wystawa czynna do 28.09.2025

Kurator: Bartosz Nowak

ENGLISH VERSION BELOW

Osoby artystyczne:

Pelka Atys

Janina Bużko

Agata Buchalik-Drzyzga

Borczi

Julia Ciunowicz

Ewa Dąbkowska

Teresa Kądziela

Kiju Klejzik

Natan Kryszk

Krystyna Mieszkowska-Dalecka

Helena Minginowicz

Mrozia11

Gosia Mycek

Anna Olczyk-Kocikowa

Natalia Piontek

Małgorzata Piekarska-Nelke

Olivia Rosa

Maksymilian Rzontkowski

Romana Szymańska-Plęskowska

Henryka Zaremba

Gryzelda Żelazny-Strączek

Wstęp

Wełni się, kłębi gdzieś historia, blisko i daleko, gdy schowana dobrze, tu i tam. Do siedemnastowiecznej historii mazońskiej docierać trzeba nitka po nitce. Zachowana w tkaninie, od wieków siwiała w ponadludzkim spokoju.

Współcześnie, dzięki badaczkom post-polskiej antropoarcheologii feministyczno-queerowej, mamy

dostęp do coraz liczniejszych acz wciąż zakurzonych źródeł ikonograficznych, które podają, że uprzednio szanowane Mazonice, wełnogłowe baby a także rozczochrane osobiszcza, po utracie matriarchatu, zmuszone zostały do ukrywania się w lasach wraz ze szczerbatymi bździągwami, tymi, co podobno czarowały, i które przetrwawszy sądy i tortury, zostały wygnane z domów i wsi.

Analiza pierwszych tkanin wykazała, że żyły razem po cichu i gromadnie. W zagajnikach i gąszczach zbierały siły, badały rośliny i przecierały szlaki, wspierały, kłóciły się i godziły, szukając sposobów na przetrwanie oraz pomstę krzywdy i niesprawiedliwości. „Zrobić na szaro wroga!”, oto była ich ledwie co ratyfikowana agenda: tkając zapisać, przechować i przekazać słowo, legendę, wiedzę, technikę. Niepotulnie tkać i nie budząc podejrzeń żyć wspólnie, na peryferiach patriarchalizującego się społeczeństwa rządzonego przez ogół mężów najgorliwszy, który wspierany przez państwa ościenne, doprowadził de facto do likwidacji matrylinearnej kultury mazońskiej obecnej na terenach współczesnej Polski od VI wieku oraz chrystianizacji wszystkiego-co-da-się, od ciał ludzkich po ciała zwierzęce i roślinne.

Peryferyk I: tracenie

Grubymi nićmi szyta historia mężnych mężów, których formalne panowanie nastało po upadku hegemonii mazońskiej szczyci się zwycięstwami niesłychanymi, a jednak takie pokątne triumfy mają więcej coś z wielkiej dziury do łatania niż wygodnego, wełnianego kontusza. Gdy historia zaczyna się od zdrady, zdrada jako początek wszystkiego nie wróży jej nic dobrego, tylko jęk, niesprawiedliwość i lęk.

To małżonek Barbary Radziwiłłówny okazał się być tym, który pogrzebał na wieki mazońską kulturę. Mianowany na marionetkowego króla przez państwa ościenne, zachłysnął się jak mocnym trunkiem z pigwy nowo zdobytym prestiżem w świecie spraw orężnych i tak zaprawiony obserwował z daleka, ukontentowany samospełniającą się zemstą, agresywną implementację chrześcijaństwa maskulinistycznego na terenach, gdzie dotychczas dzierżyły władzę Mazonice.

Jak dowiadujemy się z szesnastowiecznej mazońskiej prozy tkanej cudem jakimś zachowanej i wciąż analizowanej, potraktowana jak barbarzyńca z waginą, niemężny niemąż, Barbara Radziwiłł, uznawana za ostatnią rządzącą Mazonicę, nie mogła zrobić nic więcej niż wykląć męża oraz wraz z ich wspólnie odchowanym orlątkiem, czmychnąć bezzwłocznie gdzie zioła i czerwone maki, najczerwieńsze, rosły1.

Wyobrażać sobie można, że Barbara Radziwiłł wzięła nogi za pas histerycznie. Nic mylnego: ostatnia rządząca Mazonica była osobą nie tylko światłą, ale i szelmowską. Zanim uciekła, poukrywała po głębokich i wilgotnych piwnicach, których usytuowanie znała ona tylko, obrazy i tkaniny uznane za najświetniejsze przykłady późnej ikonografii mazońskiej. Jedno z ocalałych płócien, zagrzebane w jedwabne żupany i bufiaste szarawary skradzione bezczelnie przez nią z szaf magnackich, zostało odnalezione po przeszło dekadzie intensywnych wykopalisk. Jest to portret siostrzany o tytule „Zapleciny”. Odszyfrowanie kompleksowych elementów wizualnych obrazu nadal trwa, istnieje jednak kilka możliwych ścieżek analizy jego ogólnej symboliki.

Motyw włosów powraca regularnie w słowie i obrazie mazońskim. Plecenie, rozczesywanie, ciągnięcie to często reprezentowane banalne czynności dziennej toalety Mazonic, które, zaszyfrowane na płótnie lub tkaninie, posiadają szersze znaczenia i odwołują się do ich społecznej kultury przedpatriarchalnej. Włos pozwala pleść warkocze wspólnie z innymi kobietami; włos ramiona łaskocze, drażni i denerwuje. Włosy można głaskać z miłości albo ciągnąć z nienawiści. Symbolizują one raz wspólnotę, raz waśnie, raz dobrego ducha, raz wredotę.

Mazonice były osobami szalenie ekspresywnymi. Szczere do bólu i intensywnie kochające, mściły się łatwo na kompankach, które swoimi działaniami ujmowały prestiżowi rygoru mazońskiego. Gdy pada pytanie o to, dlaczego jedna z dwóch sióstr ma na obrazie zamazaną twarz, dwie odpowiedzi są, de facto, możliwe:

W zwyczaju mazońskim było zastanawiać się nad wizerunkiem ludzkim i rytuałami jego reprezentacji, takimi m.in. jak malowanie, rysowanie, zapamiętywanie. Kobieta, która miała zostać przedstawiona na płótnie (najczęściej do pozowania wybierane były osoby kapłańskie reprezentujące mądrość Mazonic) mogła zdecydować czy chce „oddać” swoją twarz historii oraz sztuce i pozwolić swojej podobiźnie trwać na płótnie czy jednak pozostawić ją w cieniu i zamalowaniu. Wiele zależało od kapłanek: spora część kobiet w społeczeństwie mazońskim była skopofobiczna i unikała ujawnienia pędzlem swojego oblicza. Prawdopodobnie jedna z sióstr z obrazu odmówiła „oddania” twarzy, bojąc się, że przez kolejne setki lat będzie zapleciona w sidła mistycznej obserwacji ludzkiej. Mogła liczyć na drugą siostrę, także kapłankę, która przez nią, z wdzięczności czesana, dumnie spoglądała z płótna na osoby patrzące na nią dziś i przez kolejne dni i lata.

Scenę „Zaplecin” można tłumaczyć także z punktu widzenia zemsty. Siostra czesząca, której loki na twarzy wydają się w tej wersji wydarzeń kręcić zjadliwie i ponuro, mogła była zdrajczynią, której egzystencję wśród Mazonic trzeba było, w akcie krwawego rewanżu (siostra czesana trzyma w palcach szkarłatną koniczynę), wymazać, wydrapać na zawsze.

Gdy świat drży we mgle od zmian, w duszy wrze złość na rzeczywistość. Zima szczypie nosy, na pobladłych powiekach osiadają nisko chmurzyska, mżawka drwi sobie z futer i wełnianych płaszczy. Osadza się szadź na bladych gałązkach czeremchy, zimne kropelki spływają z loczków. Kapuśniaczek przykleja się damom do policzków, świeci na ich obliczach tak szczerze prawie jak błyszczą kryształy w mazońskich skarbcach. Choć ich przyszłe losy jeszcze nie są im znane, Mazonice przeczuwają, że to już czas i niemal koniec czegoś pewny.

Matka, która czyta przyszłość z płatków ciemiernika purpurowego (jest to apokaliptyczna wersja wyliczanki kocha-lubi-szanuje-nie·chce-nie·dba-żar-

tuje), potęguje u wszystkich napięcie odczuwane w kościach. Babka niepokoi się o orlice, zapytuje w ciszy głucho gdzie je ukryć, a osóbka dziecięca powstrzymuje od szlochu: ciemiernik wcześniej był lekiem nasercowym dla starszyzny, teraz staje się wskaźnikiem przyszłych waśni i walk stanowych o przetrwanie.

Trzypokoleniowa rodzina zamieni niebawem drogocenne kryształy i przywileje decydowania o sobie w każdej chwili, o każdej porze, na bezsenne noce, tułaczkę, las i bezdroże. „Ciężkież to na mnie będą peryjody/Gdy sobie wspomnę na owe swobody”: Chryzostomowy staro-mazoński aforyzm osadzi się ciężko na świadomości szlacheckiej, a szczególnie na sumieniu skrzydlatej Husarii, której zarozumiałość stanowa okaże się być główną przyczyną upadku decentralizowanej przez lata władzy mazońskiej. Osoby badające XVI wiek zwracają uwagę na wysokie rozwarstwienie społeczne Mazonic powodowane coraz głębiej pogłębiającym się kryzysem ekonomicznym oraz wojskowym: chytre Husarki nadawały sobie przywileje, zagrabiały fortunę dworu mazońskiego, łupiąc pogardliwie stan chłopski, który, uznany za nieświadomy swojej sytuacji politycznej, nie potrafi się zjednoczyć w walce o terytorium.

Było to myślenie oderwane od rzeczywistości, obskuranckie, pyszne i nieznośne. Husarki nie miały zielonego pojęcia o egzystencji chłopskiej, która nierzadko była zielona właśnie i zielska, owijająca się w logiczną, nieprzypadkową pętelkę. O ziołach, ciałach i planetach wiedziały więcej niż większość kapłanek. Gdy nastąpiła wielka ucieczka mazońska, to chłopki najlepiej poruszały się wśród nieprzemierzonych dotychczas chaszczorów, wytyczając drogi w trakcie peregrynacji, która dla najbardziej uprzywilejowanych Mazonic, wciąż w żałobie po życiu w luksusach, w pudrze, różu i karykaturalnie smutnych łzach, wydawała się paskudnie

ponura i bezsensowna.

Na jednym z zachowanych obrazów przedstawiona została zielarka Labajka, opisana w historii kłamliwie, bo stereotypowo, jako mierna i złośliwa złodziejka ziół dworskich. Tymczasem Labajka, zdolna bździągwa, posiadała mandarynkową aurę, odczuwalną wyłącznie przez osoby chłopskie

czarująco czarujące.

Chłopki opiekowały się również orlicami, które uważały za równe sobie kompanki. Tradycyjnym wytchnieniem po długich wędrówkach było wspólne tulenie się i zasypianie. Te długopiórne, latające stworzenia stanowiły także niezaprzeczalne zagrożenie dla wrogów matczyzny, o czym nie wiedziały jeszcze mazońskie szlachcianki, przez wieki traktujące te dostojne ptaki jak najdroższą z porcelanowych zabawek, ukrywając je tu i tam, nie zdając sobie sprawy, że na wsiach to są naprawdę drapieżne ptaszory, wyszkolone w sztuce wojennej.

Z nowo odkrytych obrazów dowiadujemy się, że orlice szybko stały się jednym z filarów międzystanowej obrony leśnej Mazonic. Krążyły nad mężnymi mężami i wyłapywały sokolim chmurnookiem momenty mężności miernej, nurkując błyskawicznie na poziom skupisk pupich by udziabać prosto w krzyż maskulinistów. W konsekwencji, orlice były systematycznie prześladowane przez patriarchów augustowskich. Pamięć każdej poległej orlicy w walce trzeba było uczcić. Stąd także systematyczne ich przedstawienia w sztuce exodusowej: tematy takie jak obejmowanie, pielęgnowanie i chowanie odnajdujemy w ikonografii regularnie. Dziś badaczki post-polskiej antropoarcheologii feministyczno-queerowej obrały sobie za cel stawianie im pomników nieznanych orlic na terenach wiejskich i miejskich.

Peryferyk II: błądzenie, osadzanie

Szesnasty wiek w historiografii mazońskiej jest erą tracenia, wiek siedemnasty błądzenia i osadzania się. Jest to pewnie jedyne pewne zapewnienie, literackie bardziej niż naukowe, może nawet mniej pewne niż pewne, a może nie.

W augustowskich księgach królewskich zapisano zgon Radziwiłłówny na rok 1551 i było to potężne szachrajstwo. Dziś szacujemy, że Mazonica żyła ponad sto lat, a i więcej bodaj: w poezji pleciono-tkanej przedstawiana była w wieku siedemnastym jako persona wielowieczna, która smyrała uszy przyszłych, bezstanowych, równych sobie Wełnogłowych opowieściami o przeszłości, wplatając w nie wymyślone bajeczne, acz zramolałe, złote myśli. Person wielowiecznych w leśnej ikonografii było zresztą znacznie więcej, stanowiły one rdzeń odradzającej się, w warunkach polno-polowych, wielopokoleniowej i wielopłciowej niemężnej kultury mazońskiej. Stąd też regularne przedstawienia matek z osobami dziecięcymi. Łatwo zauważyć jak zmieniają się użyte do portretów materiały: po kilkudekadowym uchodzeniu kobiet z dworów i dworków i wsi oraz powolnym osadzaniu się w lasach, brakowało Mazonicom płócien i czystej wełny. Sztuka mazońska opierała się coraz bardziej na wytwórstwie z włókien roślinnych, strzępków ubioru i płóciennych sakw. Z tych powodów właśnie analiza dalszej części historii, czyli przede wszystkim początku wieku siedemnastego musi opierać się dziś na odszyfrowaniu narracyjnym ściegów i symboli wizualnych.

Wraz z exodusem zaczęła się bolączka wędrowcza Mazonic: w bezgłosie, przez wysokie pasma górskie, po gołoborzach, w bujnych zaroślach, maszerowały, wpadały w bagna, potykały o czarcie kamyczki na prostej drodze. Ich pokute przez osty i pokrzywy nogi dźwigały ciężką zbroję a styrane barki i ręce niosły i kryły te istoty, które im były najdroższe: orlątka i kocięta.

Przy wchodzeniu w las pejzaż nie był nawet zielony: gorączka przepalała zmysł widzenia, lasy płonęły czerwienią i oślepiały raz po raz ciemno-błękitnymi błyskami w chaszczo-gęszczach i zielskach. Gałęzie i kolce przyczepiały do włosów i szyj, wysokie chwasty wgryzały w brody, przypominając w przerażającym półszepcie: „Zgryzota jest i będzie, szukajcie bab wełnianych i bźdzwiągw wszędzie a pomoc będzie.”

Po długich dniach wędrówki Mazonice wpadały w stan drzemkowego marazmu pragmatycznego, rozluźniając kończyny, rozpłaszczając swoje członki. Najbezpieczniej było drzemać na łąkach na płasko i na twardo pod różowatym, dzikim księżycem.

Wśród bzyczących istot nieludzkich, przed zaśnięciem, kobiety nuciły pod nosem mazońskie pieśni, wzywając duchy towarzyszek niedoli, które straciły życie podczas tułaczki. Przetrwanki zdawały sobie sprawę, że zostawiwszy na zawsze majątek cały we wtedy już patriarchalnej krainie, zdane były na najniebezpieczniejsze starania o kilka marnych, brzęczących groszy, takie jak żebractwo czy zarobek seksualny. W nowo-powstałym społeczeństwie mężnych mężów, biernie lub aktywnie chrześcijańskich, ubóstwo i seksualność kobiet oraz osób niemężnych były największymi tabu, krwawo karanymi.

Najbardziej aktualne, choć wciąż kontrowersyjne prace ikonologiczno-narracyjne mówią, że pod koniec wieku siedemnastego Mazonice, po długich poszukiwaniach, odnalazły sposób na porozumienie się z Wełnogłowymi przetrwankami i bojowniczkami wiejskimi, jak Bogna z Wartowskiej Mgiełki. W pobliżu Łysej Góry, gdzieś w paśmie Łysogór, zwoływały walne zgromadzenia, podcinając tym samym skrzydła Husarkom, które już nie musiały latać. Orlice mogły kontynuować ich uprzednie zwycięskie misje zwiadowcze i rozbójnicze na własne skrzydło.

Po kilkunastu latach sabatów, po swarach i waśniach, wrzeniach i buntach zdecydowano ostatecznie, że chłopkom szlachcianki nacierać będą wieczorami styrane plecy kropelkami rosy. Można uznać taką decyzję za czegoś zaczyn, początek przyszłości bez-, lub właściwie, transstanowej. Czekamy wciąż na najnowsze analizy źródeł wizualnych z XVIII wieku, by móc snuć o tym malowane historie, pleść głupotki czy pisać peryferyki. Na marginesach historii utkane są zawsze gdzieś jakieś tajemnice.

Gryzelda Żelazny-Strączek

1I nie było w tym nic dziwnego, że maki tak najczerwieniej się rumieniły, bowiem „zamiast rosy piły ’zońską krew”. Tkany i malowany na płótnach mit opowiada, że prababki i babki, praosobiszcza i osobiszcza karmiły maki alpejskie własną krwią menstruacyjną, która, jak wierzyły, miała właściwości magiczne, moc znieczulającą. Po dekadach czerwienienia (w setkach liczonych), maki wzrosły na szkarłatne. Współcześnie rozumiemy, że maki te, które dziś co więcej uznawane są za najpospolitsze polskie Papaver rhoeas, związane były symbolicznie z bezkompromisowymi ćwiczeniami wojennymi Mazonic, najczęściej na łąkach, gdzie obficie rosły. Zrywane po długoletnim zraszaniu, używane były leczniczo przeciwko intensywnym bólom menstruacyjnym podczas wojaczki.

Julia Woronowicz (ur. 1997 w Warszawie) – artystka wizualna i performerka, znana również jako Pola Nuda. Tworzy jedną, wielowątkową opowieść – spekulatywną historię alternatywną, w której dziewczynki, kobiety, rośliny i inne istoty odzyskują miejsce w czasie. Jej prace to etnofikcyjne kroniki świata, który mógłby istnieć – i może w ogóle istnieje – poza oficjalną historią. Zdobywczyni potrójnej nagrody specjalnej w konkursie Najlepsze Dyplomy ASP 2023 w Gdańsku za pracę „Tkanina wildecka” (Nagroda specjalna CSW Łaźni, Nagroda Krytyków, Wyróżnienie honorowe), zdobywczyni potrójnej nagrody specjalnej w 43cim konkursie im. Marii Dokowicz w Poznaniu za pracę „Tkanina wildecka” (Nagroda specjalna prezydenta miasta Poznań, Nagroda specjalna NN6T (magazynu Notes na Sześć Tygodni, Nagroda specjalna marki Solar; (2023). Zwyciężczyni oraz laureatka nagrody specjalnej Artystycznej Podróży Hestii (2021). Dwukrotna magistra sztuki (rzeźba, Warszawa oraz intermedia, Poznań), finalistka Strabag Kunstforum i Bielskiej Jesieni 2023. Rezydentka RU w Nowym Jorku w 2022, Nobody’s baby w Wiedniu w 2025. Jej prace były wystawiane m.in. w Zachęcie, MSNie, PGSie, lokalu_30, Narodowym Muzeum Sztuki w Kiszyniowie, flat1 w Wiedniu i Ki Smith Gallery NYC.

Introduction

Tangled wool. History, even when well hidden, somewhere twists and coils, somewhere both near and far, here and there. One can only unravel the story of seventeenth-century Masovians thread by thread. Preserved in fabric, it has been greying for centuries in an almost supernatural tranquility.

Today, thanks to researchers in post-Polish feminist-queer anthropo-archaeology, we have access to an increasing number of albeit still-dusty iconographic sources. These detail how the once respected Masovians—wool-women and tangled-haired creatures—after the loss of their matriarchy, were forced to hide in the forests alongside those gap-toothed hags who purportedly practised witchcraft and whom, having survived various tortures and trials, found themselves banished from their homes and villages.

Analysis of the earliest textiles showed that the Masovians lived together, quietly and communally. In groves and thickets they gathered their strength, studied plants and cut new paths through the wilderness. Supporting one another through quarrels and reconciliations, they sought ways to survive and avenge the injustices they had suffered. “Outsmart the enemy!” This was their freshly sworn pact: through weaving to record, preserve and transmit word, legend, knowledge, and technique. To weave defiantly, and to live communally, without drawing attention or suspicion, on the peripheries of a society that was becoming ever more patriarchal, ruled over by the most zealous assembly of men who, supported by neighbouring states and kingdoms, brought about the de facto extermination of Masovian dubious culture—a culture that had been present in the domains that now make up modern Poland since the 6th century—as it went about the Christianisation of everything-that-could-be-Christianised, from human bodies to those of plants and animals.

Periphery I: losing.

This history stitched in coarse thread by those valiant men, whose formal reign began with the fall of Masovian hegemony, boasts of unprecedented victories. Yet these dubious triumphs have more in common with a wide hole in need of patching than a comfortable woollen overcoat. When a history begins with betrayal, that betrayal—as the origin of all that follows—promises nothing good, but only wailing, injustice and fear.

It was the spouse of Barbara Radziwiłł who turned out to be the one who buried Masovian culture forever. Appointed as a puppet king by neighbouring states, his newly acquired prestige in the world of martial affairs intoxicated him as if were a heady quince liqueur. Thus fortified he was happy to watch from a safe distance as his vengeance unfolded of itself through the aggressive prosecution of a masculinised Christianity in those territories the Masovians had hitherto held power.

As we learn from the woven prose of sixteenth-century Masovian artefacts—miraculously preserved and still in the process of being analysed—Barbara Radziwiłł, considered a barbarian with a vagina, an unmanly non-male, as well as the last ruling Masovian, could do nothing more than curse her husband, take the eagle they had raised together, and flee to where the herbs and the red poppies—the very reddest1 —grew.

One might imagine that Barbara Radziwiłł took to her heels in a state of frantic hysteria. Nothing could be further from the truth. The last ruling Masovian was both cultured and cunning. Before she fled, she took the paintings and textiles—considered the finest examples of late Masovian iconography—and hid them in deep, damp cellars, the locations of which were known only to her. One of the surviving canvases, buried among silken long coats and puffy trousers (which she had brazenly stolen from a magnate’s wardrobe), was discovered after more than a decade of intensive excavations. It is a portrayed portrait entitled, Braiding. The deciphering of this painting’s complex visual elements is ongoing, but there are several possible ways to analyse its overall symbolism.

The motif of hair returns regularly in Masovian text and image. Everyday grooming activities such as tugging hair, braiding or combing it, are often represented. Which when encoded on canvas or in fabric possess a broader meaning, and refer directly to their pre-patriarchal society and culture. Hair is braided communally, in the company of other women. Hair tickles the shoulders, irritates and annoys. Hair can be stroked with love or pulled with hatred. It can symbolise community, strife, good spirits, and/or malice.

The Masovians were an intensely expressive people. Painfully honest and intensely loving, they were quick to punish any of their companions whose behaviour they felt undermined the prestige of Masovian code. When the question arises as to why one of the two sisters in this painting have their face blurred-out, two answers are, de facto, possible:

It was a Masovian custom to reflect upon the human image and the rituals of its representation, as in painting or drawing, or in other methods of preservation in memory. A woman who was to be representative on canvas (more often than not a priestess was chosen as representative of the wisdom of the Masovian) could choose whether or not to ‘give’ her face to history and to art, she could choose whether to allow her likeness to survive on canvas, or have it obscured in the shadows, blurred or otherwise painted out. Much depended on the priestess: a significant number of women in Masovian society were scopophobic, and so it would not have been unusual for a priestess to have kept their face from the painter's brush. It is probable that one of these sisters refused to ‘give’ her face to the painting, fearing that centuries of strangers would hold her captive with their stares. She could count on the other sister (also a priestess) whose hair she combs out of gratitude, and who looks out with pride at all those who look back at her today, and for all the days and years to come.

The erasure in the Braiding could also be understood from the standpoint of revenge. The combing sister, whose curls (in this version of the events) seem to twist with venom and gloom, could have been some traitor whose existence the Masovians felt compelled to erase and scratch out forever in an act of bloody vengeance—the sister being combed does hold a scarlet clover in her fingers.

When the world trembles in the fog of change, anger at reality seethes in the soul. Winter bites at the nose, low clouds weigh upon pale eyelids, while drizzle mocks fur coat and woollen cloak alike. Hoar frost settles on pale bird-cherry branches, ice-cold droplets run down ringlets of hair. Fine rain adheres to the cheeks of fine ladies, their faces shining with almost as much sincerity as the crystals sparkling in Masovian treasure chambers. Though they know not their ultimate fate, the Masovians must sense that their time has come, that something is undeniably ending.

The mother, who reads the future from the purple petals of the hellebore (an apocalyptic version of the children’s rhyme “they love me, they love me not”), heightens the tension they all feel in their bones. The Grandmother worries about the she-eagles, and asks herself quietly where to hide them; the child-person holds back their tears. Hellebore was once a heart medicine for the elders, now it has become an indicator of future conflicts and class struggles for survival.

The three‑generation family will soon trade in their precious crystals—and with them the privilege of self-determination in every moment, and at any time—for sleepless nights and wandering, for forest and trackless wastes. “Heavy will those times be upon me / When I recall those freedoms”, this Chrysostomian old-Masovian saying will settle heavily upon their noble consciousness, and especially on that of the winged Hussars, whose class conceit will prove to be the main cause of the fall of Masovian power, which had been decentralised for years. Scholars studying the sixteenth century point to the high social stratification among the Masovians brought about by a worsening economic and military crisis. Cunning Hussar women bestowed privileges upon themselves, plundered the fortune of the Masovian court, contemptuously pillaging the peasantry, which they considered politically unaware and incapable of uniting in the struggle for territory.

This thinking was detached from reality, obscurantist, proud and insufferable. The Hussar women were utterly green [clueless] about peasant existence, which was itself genuinely green and herbal - a fitting irony. Peasant women knew more about herbs, the body and the planets than most priestesses. When the great Masovian flight began, it was the peasant women who best navigated the hitherto untrodden thickets, marking out the way during the peregrination, which for the most privileged Masovians—still mourning their life of luxury, their powder and their rouge, with tears that were mere caricatures of sorrow—seemed hopelessly grim and pointless.

One of the preserved paintings depicts the herbalist Labajka, described in history falsely, stereotypically, as a mean and spiteful thief of the nobles’ herbs. In truth Labajka, a gifted hag, possessed a mandarin aura, perceptible only to the peasant folk who practiced the craft.

The peasant women also cared for the she-eagles, which they considered their equals. After wandering long and hard, it was their custom to nestle down with them and fall asleep. These long-feathered, flying creatures also posed a clear threat to the enemies of the motherland, a fact the Masovian noblewomen were as yet unaware of, having for centuries treated these noble birds like the most expensive of porcelain miniatures, hiding them away, not realising that among the peasantry these were genuine birds of prey, trained in the art of war.

Newly discovered paintings reveal that she-eagles quickly became crucial to the forest defence that united all Masovian classes. They would circle above the valiant men and, with their sharp hawk eyes, identify moments of mediocre manliness, diving lightning-fast to buttock height to strike directly at the tailbones of the masculinists. As a result, the she-eagles were systematically persecuted by these Augustan patriarchs. The memory of every she-eagle that fell in battle had to be honoured, hence their consistent representation in the art of the exodus—motifs such as embracing, nurturing and burying are found repeatedly in the iconography. Today researchers of post-Polish feminist-queer anthropo-archaeology have made it their purpose to erect monuments to unknown she-eagles in both rural and urban settings.

Periphery II: wandering, settling.

The sixteenth century in Masovian historiography is an era of loss, the seventeenth of wandering and settling. This is probably the only certainty, more literary than scientific - though perhaps not even certain at all. Or perhaps it is.

In the Augustów royal archives the death of Radziwiłł was recorded in the year 1551. This was a monstrous fraud. Today, we surmise that this Masovian lived for one hundred years, and perhaps even longer. In the braided and woven poetry of the seventeenth century she was portrayed as an ancient figure who told stories to later generations of wool-women—those who would live in equality without class distinctions—tales of the past, intermingled with made-up fairy tales and worn-out pearls of wisdom. There were many more centenarians reproduced in the forest iconography. These figures formed the core of a reborn multi-generational and multi-gendered anti-masculinist Masovian culture, one set amongst the fields and meadows. These regularly depicted mothers and child-persons. There is though a marked and obvious change in the materials used in these portraits. After several decades on the run, these women who had taken flight from their courts, manors, and villages to settle in the forest, were short of canvas and pure wool. Masovian artwork came to rely increasingly on plant fibres, scraps of clothing and canvas from sacks. Because of this shift, analysis of the later history—particularly the early seventeenth century—now depends on decoding the narrative in the stitch-work, as well as the symbolic visual imagery.

With the exodus began the Masovians’ itinerant hardship, a hardship borne in silence. They marched across high mountain ranges, through dense undergrowth, and over stony ground, they fell into marshes and bogs, and stumbled over devilish pebbles on the unbending road. Their legs, scratched and stung by thistles and nettles, bore the weight of heavy armour, while their weary arms held—and concealed—the creatures dearest to them: eaglets and kittens.

As they entered the forest, nothing was green to their fevered eyes: the woods burned crimson, and flashed dark-blue through dense thickets and weeds. Thorns and branches caught in their hair, tall weeds raked their faces, reminding them in a terrifying half-whisper, “Sorrow is and ever shall be—seek the wool-women and the wise-women everywhere, and help will follow.”

After long days on the road, the Masovian women would fall into a weary, instinctual torpor, loosening their limbs and spreading themselves flat. It was safest to doze in the meadows, level and hard, beneath the wild pinkish moon.

Amid the buzzing of non-human life, before sleep, the women would hum Masovian songs under their breath, calling upon the spirits of their erstwhile companions in this misery, those who had already lost their lives to the meandering journey. Having left their entire fortune behind them in what was by then a patriarchal domain, the survivors knew that they were condemned to the most perilous of occupations to scrape together a few jingling pennies, namely begging or sex work. In the newly-formed society of valiant men, regardless of whether it were actively or passively Christian, the poverty and sexuality of women and non-male persons were the gravest of taboos, and transgressing those taboos was punished with bloodshed.

The most up-to-date, though still controversial, iconological readings of the narrative sources state that, by the late seventeenth century, after long searching, the Masovians found a way to reach an understanding with the surviving wool-women and rural fighters, such as Bogna of Wartowska Mgiełka. Near Łysa Góra, somewhere in the Łysogóry mountain range, they convened general assemblies, effectively grounding the Hussar women who no longer needed to fly. Their eagles free to continue their proven scouting and raiding missions on their own terms.

After so many years of sabbaths, quarrels, feuds, ferment and rebellions, it was finally decided that, in the evenings, the noblewomen would anoint the peasant women’s worn backs with drops of dew. Such a decree could be considered the beginning of something, of a future that might be classless, or rather, trans-class.

We’re still waiting for the release of the latest analyses of the visual sources from the eighteenth century, only then can we spin our painted histories, indulge in our nonsense, or scribble in the margins. Secrets are always woven somewhere in the margins of history.

Gryzelda Żelazny-Strączek

1 And there was nothing odd about the fact that poppies blushed so redly, for “instead of dew they drank women's blood”. This myth—woven into, as well as painted on, canvas—tells the story that grandmothers and great-grandmothers, ancient figures and more recent ones, fed alpine poppies with their own menstrual blood, which they believed had magical properties and an anaesthetic power. After centuries of reddening, the poppies grew scarlet. Today, we understand that these poppies (which moreover are now designated as the common Polish Papaver Rhoeas) were symbolically connected with the brutal military training of the Masovians, typically conducted in those meadows where these poppies flourished. Plucked, after years of being sprinkled upon, poppies were used medicinally during warfare to combat intense menstrual pains.

Julia Woronowicz (b. 1997, Warsaw), also known as Pola Nuda, is a visual artist and performer who creates speculative alternative histories where girls, women, plants and other beings reclaim their place in time. Her ethno-fictional works chronicle worlds that might exist—or perhaps do exist—beyond official history.

Woronowicz received triple special awards at the Best Diplomas ASP 2023, Gdańsk for "Wildeck Fabric" (CSW Łaźnia Special Award, Critics' Award, Honorary Distinction) and triple special awards at the 43rd Maria Dokowicz Competition, Poznań for the same work (Special Award of the Mayor of Poznań, NN6T Magazine Special Award, Solar Brand Special Award, 2023). She won the Hestia Artistic Journey special award (2021). She holds MFAs in Sculpture (Warsaw) and Intermedia (Poznań), and was a finalist for Strabag Kunstforum and Bielska Autumn 2023.

Her work has been exhibited at Zachęta National Gallery of Art, Museum of Modern Art (Warsaw), Polish Sculpture Gallery, lokal_30, National Museum of Art (Chișinău), flat1 (Vienna), and Ki Smith Gallery (NYC). Woronowicz was a resident at Residency Unlimited, New York (2022) and will be at Nobody's baby, Vienna (2025).

od lewej: Oliwia Rosa, Waza; Ewa Dąbkowska, Tęczowa stuła; Julia Woronowicz, Przebiegła husarka Marlena

.jpg)

_mid.jpg)

_mid.jpg)

_mid.jpg)

_mid.jpg)

_mid.jpg)

_mid.jpg)

_mid.jpg)

_mid.jpg)

_mid.jpg)

_mid.jpg)

_mid.jpg)

_mid.jpg)

_mid.jpg)

_mid.jpg)

_mid.jpg)

_mid.jpg)

_mid.jpg)

_mid.jpg)

_mid.jpg)

/fb_png.png)

.png)

/karta_png(1).png)

.png)

.png)

.png)